About Storer

Notes on the Origins of Storer College

The following is compiled from a comprehensive history of Storer College by Shepherd University history professor Dawne Raines Burke. Readers interested in exploring Storer College’s history and legacy in greater detail are referred to Professor Burke’s groundbreaking book An American Phoenix: A History of Storer College from Slavery to Desegregation, 1865-1955 which will be reissued in a new commemorative edition by Storer College Books on June 19, 2015, as part of the West Virginia University Libraries 2015 West Virginia Day Celebration.

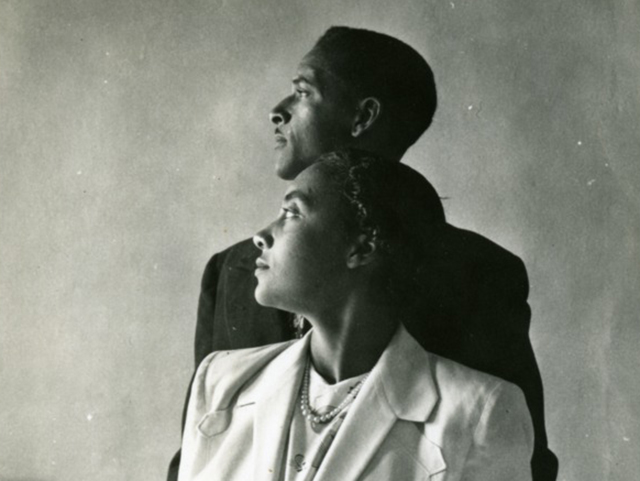

A profile portrait of a young man and woman who were students at Storer College.

In Antebellum Virginia, educational opportunities for African Americans were not only lacking; they were forbidden by law! Whites found guilty of teaching slaves were subject to fine, imprisonment, or both. Their pupils faced lashing or even death. Educational pursuits by even free blacks were a civil offense leading to forfeiture of Virginia residency and banishment from the state.

Given this history, it is easy to understand why the establishment of a school for African Americans in Harpers Ferry, one hundred and fifty years ago, was a pivotal event in West Virginia and American history. Eventually named Storer College, this institution would educate more than 7,000 students during the course of its 90 plus year history.

The origins of Storer College rested in a determined effort by the Freewill Baptist Church to provide an education to as many emancipated slaves as possible. A New England denomination, the first Freewill Baptist church was established in 1770 in New Durham, New Hampshire by Benjamin Randal, a George Whitefield convert. Whitefield, a British evangelist associated with the religious revival of the Great Awakening and influenced by the Age of Enlightenment, made several trips from England to Colonial America during the mid-eighteenth century. Reverend Whitefield became the model for the evangelical fervor and missionary zeal of the Free Will Baptists whose founders were indeed "reawakened" and "enlightened" to a greater sense of moral principle and social obligation through critical, autonomous reasoning.

Nearly one hundred years later, the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 triggered an ambitious thrust by the Freewill Baptists, who had expanded their reach throughout New England and beyond, to help relieve the plight of freed slaves through education. The denomination, which had spread throughout New England and beyond, proceeded to found mission schools throughout the Shenandoah Valley. Free Will Baptist members readily and willingly relocated to the valley to establish these schools as well as a Shenandoah Home Mission Society center in Harper's Ferry. While focused initially on providing elementary education to the masses, as time passed, their ultimate goal became the establishment of college for Negroes in the south below the Mason-Dixon.

Isabelle Stewart, Raymond McNeal, and Odetta Johnson sit on the lawn at Storer College holding a school pennant in 1917.

While the Free Will Baptists and other religious organizations did much in the post-war years to establish a standardized level of education for southern freedmen, the subject also gained the attention of northern philanthropists, who became equally involved in the cause. In the case of Storer College, a key benefactor was John Storer, a Congregationalist from Sanford, Maine, who owned stores throughout the Granite State and who had also made several profitable investments. Dedicated to the goal of education, in 1867 Storer pledged $10,000 to Reverend Oren Burbank Cheney, a Free Will Baptist representative, to institute a school in the south for freedmen. Storer entered into a two-party contract with the Baptists leading to Storer College's formation. That contract included five clauses: (a) Storer's pledge was contingent upon a corresponding investment by the Free Will Baptists; (b) the sum was to be entrusted to an investment-third party for municipal bonds until the original pledge yielded $40,000; (c) the corresponding Baptist investment was to be raised on or before January 1, 1868; (d) the institution should bear the name of its greatest benefactor; and (e) the original pledge, in the event of premature death, was to automatically revert to the John Storer estate.

When John Storer died on October 23, 1867, and his heirs exercised hereditary privilege over his real property, investments, and liquid assets, the Free Will Baptists initially feared their endeavors had been undertaken in vain; however, Storer's children eventually were convinced that their father's endowment should be honored and fulfilled. They emulated their father's philanthropic model relinquishing all legal claim to his $10,000 pledge to the Baptists for the school. Later, they even donated an additional $1,000 to be used for establishing the school's first library.

The Lockwood House, one of four federally-owned buildings acquired by the founding denomination, was the first physical structure to accommodate the school under the benefactor's name, Storer College. The cannon-bombarded, abandoned house, which provided temporary accommodations for the Baptists by ordinance of the reorganized government in 1865, formerly housed both Union and Confederate officers before and during the Civil War, as Harper's Ferry passed from Union to Confederate hands and vice versa. Official acquisition of these buildings was granted, by an Act of Congress, through the War Department's Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, the federal authorization of which included the requisition and resale of abandoned properties, the supervision of freedmen activities, and provision for humanitarian aids and services.

Storer College was granted a charter by the West Virginia Legislature as "an institution of learning for the education of youth, without distinction of race or color" in 1867. The qualifying phrase "without distinction of race or color" was fiercely debated between the two legislative houses according to Free Will Baptist denominational correspondence. Those in favor of the school's broad charter believed that educational development was essential for the state's entire population, including both the state's majority and minority populations. Thus, Storer College was granted its charter as a state-approved normal department in the same year the West Virginia State Normal Department established Marshall [Academy] College in Huntington, Cabell County, as the state's first normal department for white students.

The West Virginia Legislature's vote for Storer College's charter, however, was remanded for vote until the spring session of the following year. As a result, although the institution had been in full operation under its legal name since 1867, the charter's passage was dated March 3, 1868. And thus, from what initially began as a mission school evolved a four-year college.

As noted above, Storer College went on to educate more than 7,000 students in the ensuing decades before closing its doors in 1955 due to desegregation and assorted other factors. Among its many notable graduates were J.R. Clifford (1848-1933), West Virginia's first African American attorney; Minnesota legislator John Francis Wheaton (1866-1922); pioneering pharmacist Ella P. Stewart (1893-1987); jazz legend Don Redmond (1900-1964); and Nnamdi Azikiwe (1904-1996), the first president of the nation of Nigeria. Such a legacy would make its founders proud indeed!